Kosher Soul and the Chocolate Chosen

By Jasper Colt

In the early morning sun the bright white bolls glow like freshly fallen snow on the fields of Chippokes Plantation. Though the dew has barely dried, the work has already begun. Bending low between the long rows, the cotton, stiff and sharp, catches and pulls at the legs and hands. Today, one man works this field alone. Dressed in plain, handmade cotton garments stained with food and dirt, he peers out across the vast white plains of his toil to come and wipes the sweat from his chestnut brow.

He deftly tears each fiber from the plant and sings an old song, low and slow, as it plays through the earbuds of his iPod. He is soon overcome by his communion with his ancestors and belts out a loud and piercing “Pharoah...Pharooooooooooah. Pharoah’s Army sure got drownded, Pharoah.” His sudden outburst visibly upsets Jacob, a tall young man with a long ponytail and a goatee who sits a few yards away documenting Michael's labors in the cotton field with a camera. Later, Michael explains, “Jacob is my partner, on multiple levels. We give ourselves away when we argue. He doesn’t like it when my ancestors show up and I start hollering and screaming.”

Michael William Twitty–not to be confused with the singer Michael Twitty, son of country music legend Conway Twitty–doesn't shy away from who he is. In fact, picking cotton in the fields along the banks of the James River, just across the water from Colonial Williamsburg, is part of a larger historical, genealogical and culinary exploration he dubs "The Southern Discomfort Tour." Michael’s surname comes from a family of South Carolinian slave owners to whom he may also be connected by blood and his hope is that this odyssey will lead him to share a table with the families that once held his own in captivity, to cook and eat beside them in remembrance and solidarity. Sitting before a map of the deep south in his YouTube video plea for cooperation and assistance, he exclaims, “everyone deserves to know where they come from. Everyone deserves to know their American story.” Michael’s desire to discover his roots and understand what it was like for his enslaved and free Black ancestors stems from a deep connection to his African American identity, and to food in particular.

***

In the disheveled backyard of his redbrick suburban rambler, Michael surveys the damage done to his heirloom vegetable garden by Hurricane Sandy while his two overexcited dogs frolic in the unseasonably warm November afternoon. Bent over raised beds he built himself—sometimes using discarded materials like old wooden bed frames—he grins as he picks the season’s last tomatoes, still green, from the storm beaten vines. He once said in a radio interview, “One of the first things I remember growing up was going to the garden. My grandmother had collard greens and turnip greens. The garden was huge.” This small plot of fertile hand-turned soil is more than just a source of fresh heirloom varietals for him, it is also a poignant connection to his African American ancestors and their homeland. He grows the plants that they grew so he can cook the foods that they cooked.

Food is a central component of Michael’s identity, a unifying element that connects the sometimes disparate aspects of it. His love of cooking is less about eating than it is about sharing food and history with others. This passion and his talents have led him to make a career as a culinary historian and historical interpreter of African American foodways despite the fact that “there are no B.A., M.A. or Ph.D programs in how to cook like an eighteenth- or nineteenth-century slave or how to work in a cotton, tobacco, corn or rice field." In fact, Michael is still three classes shy of the B.A. in Afro-American studies he began at Howard University, but his work speaks for itself and he is undoubtedly a historian nonetheless.

Besides making ends meet with educational programs, speaking engagements and cooking demonstrations for places such as the Smithsonian Institution, Colonial Williamsburg and the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery, Michael is also a prolific blogger and highly motivated project manager. "The Southern Discomfort Tour" is part of a larger, ongoing project he calls "The Cooking Gene." Funded by an Indiegogo campaign, he and a small group of support staff “will highlight and address his journey to trace the food-steps of his ancestors in the Old South, using the story of African American foodways to follow his ancestors from Africa to America and from slavery to freedom.”

Michael’s work is important to him personally, but even more so as a way to give back to his community. He says, “it’s very important for me to teach to African American kids, particularly young men. I see them killing each other, I see them dying and I see them not knowing their history. And if you don’t know where you come from, where you’re going is really at risk.”

***

Seated at a long table, seemingly oblivious to the several dozen middle aged white New Yorkers packing the small room, Michael flips through a pre-release copy of the Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America in search of his contributions. As he finds each one—entries on Washington, DC, Baltimore, MD, and collard greens, as well as an article on recent developments in the study of African American foodways—a smile parts his lips and he lingers on the page. As a contributor, he was invited to join a panel of experts for the book’s release party at the Institute of Culinary Education in midtown Manhattan.

Michael stands, leaning forward with his hands on the table, and addresses the audience with confidence. He talks of culinary justice and the ways that food can be utilized to rebuild broken communities and reclaim historical culture, and even gets a few laughs in the process. Watching him work the crowd with such agility, one easily assumes he has long been a leader in his field. However, without a diploma he has struggled to validate his knowledge and expertise over the years. When asked about it, he laments, “you’re told if you follow up on the rules of the meritocracy that you are essentially able to scale the walls of injustice and inequality and the way will be smooth for you, and this is a myth. My biggest struggle is to achieve parity with people who don’t look like me who are doing the exact same thing I do. Looking the part is a big deal. You would think that with the niche that I have and the way I constantly work at articulating what is unique about my work, that it would be a lot easier, more gates would open.”

Just a few hours earlier Michael stepped off a cheap bus after a four hour ride from Washington, DC, into the bright sun and frantic midday pace of a New York City sidewalk. Orthodox Jews, hot dog vendors and hipsters alike stole glances at the curious passerby—a large, well-dressed African American man dragging a roller bag and sporting an off-white yarmulke. Now he sits alone in the room where he spoke, winding down after a long evening of networking at the reception, exhausted, recharging his phone and his psyche. There is no Towncar waiting outside to whisk him away to a fluffy hotel bed. Worse still, the friend he arranged to stay with was hospitalized the night before. He trudges to the subway, luggage in tow, unsure of his way, and laboriously makes his way across the East River to a hospital in Brooklyn to visit his friend and get the keys to her house. On the verge of collapse, he finally steps into her row house well after midnight.

***

“Hi, Michael Twitty from the religious school,” he proclaims proudly as he leans toward the microphone embedded in the wall of Jerusalem stone.

A buzzer sounds and Michael gently touches the mazuza as he opens the door to Temple Beth Ami and enters another of the worlds that he routinely navigates. Wafting through the long, white corridors, the sounds of children singing the Dreidel Song mix with the twang of an acoustic guitar and the tenor of the Temple cantor. Michael settles into a colleague’s office and waits for a phone interview with a New Orleans NPR affiliate station. Meanwhile, he leans back, checks his Twitter feed, thumbs through the pages of Jewish Way magazine and sends an email to the parents of his sixth grade Judaic Studies class.

The phone rings and Michael’s face immediately lights up. This is his moment to shine, one of many brief affirmations that all he works for is worthwhile. On the other end of the line Poppy Tooker, host of Louisiana Eats, asks him how he celebrates the holiday season and Michael jokes about “ChristmaKwanaHannzukah,” explaining in culinary terms, “the food that I put out in my own personal circle and setting is an invitation to this complex identity we’ve been talking about. If people cannot understand or comprehend me on any other level, they can understand me through my plate.” Fittingly, the radio station posts a recipe for “Michael Twitty's Southern Latkes” on its website to accompany the audio stream of the story.

Michael’s conversion story is not a complex one. He grew up on the edge of a predominantly Jewish neighborhood in Montgomery County, MD, and was fascinated by the religion from an early age. He frequently relates stories of his dabbling in Judaism as a child. Once, his father took him to Colonial Williamsburg at seven years old. Michael chuckles as he remembers, “I took my tricorn hat and folded it into a yarmulke.” Another time, "I told my mother I was Jewish, and she thought that was odd, but she let me be Jewish for a week. It ended abruptly when I was told that I had to go to the doctor’s office for a certain operation.” After his conversion, he was intrigued to discover that he is “officially 8% Eastern European Jewish by DNA.”

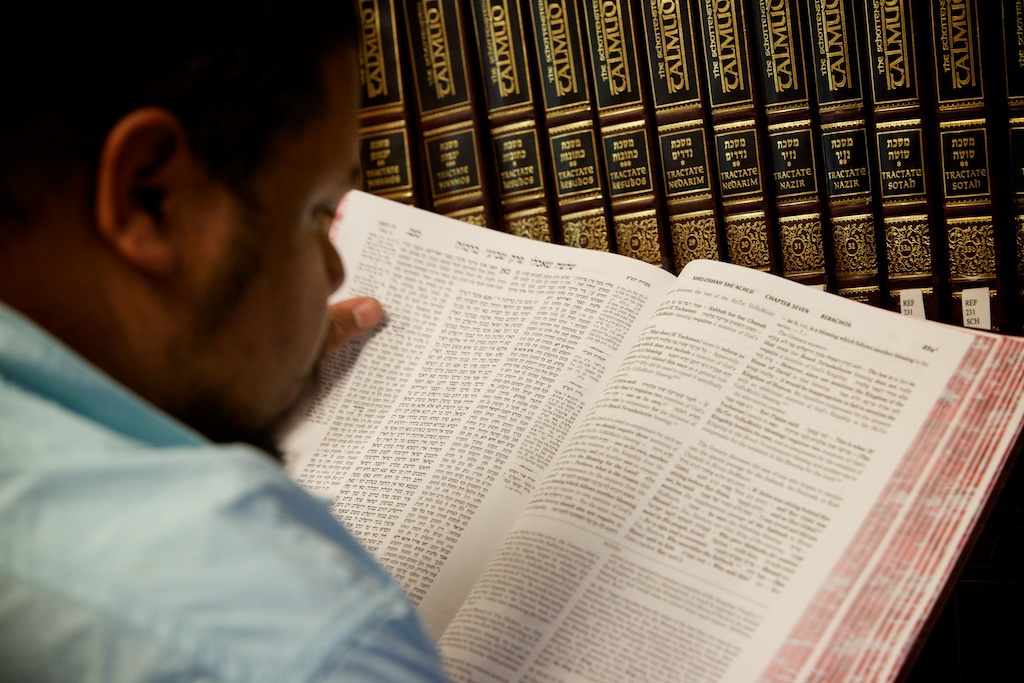

After the interview, Michael finds a few moments of quiet in the temple library and pulls large, beautifully bound tomes from the shelves. Fingering the pages pensively, he searches the Talmud for references to race and sexuality. He reads one of the passages he finds, “If one sees a negro, a very red or very white person, a hunchback or a dwarf or a dropsical person, one should say ‘blessed is he who makes strange creatures.’” He does not comment, but rather sits in silence, lost in thought on the subject.

Once the singsong of schoolchildren dies down and their parents have corralled them into idling SUVs, Michael wanders into the sanctuary for his evening prayer. He kneels alone before the ark as the evening sun streams through the expansive west-facing windows, casting an orange tint over the Torah scrolls. His soft, serious voice reverberates in the empty room as he recites the Minha with solemn reverence.

***

“It’s not about being Jewish. It’s not about being gay. It’s about being different. If you in a Black family and you different, you just keep your mouth shut. You don’t make a lotta waves. You chill out. You do what you gotta do.”

When he talks about growing up, Michael slips into what he calls the Black vernacular. Ask him about Judaism and you will invariably hear him utter words in Hebrew. Question him on antebellum southern food traditions or the club scene in DC and you’ll hear yet other vernaculars. He’s not passing, nor is he posing, this is the real Michael Twitty. He takes it all in stride and does so with an affable sense of humor, often referring to himself as one of the “chocolate Chosen,” and joking, “I chose the moniker Kosher Soul for a reason, because Colored Jew wasn’t as poetic.”

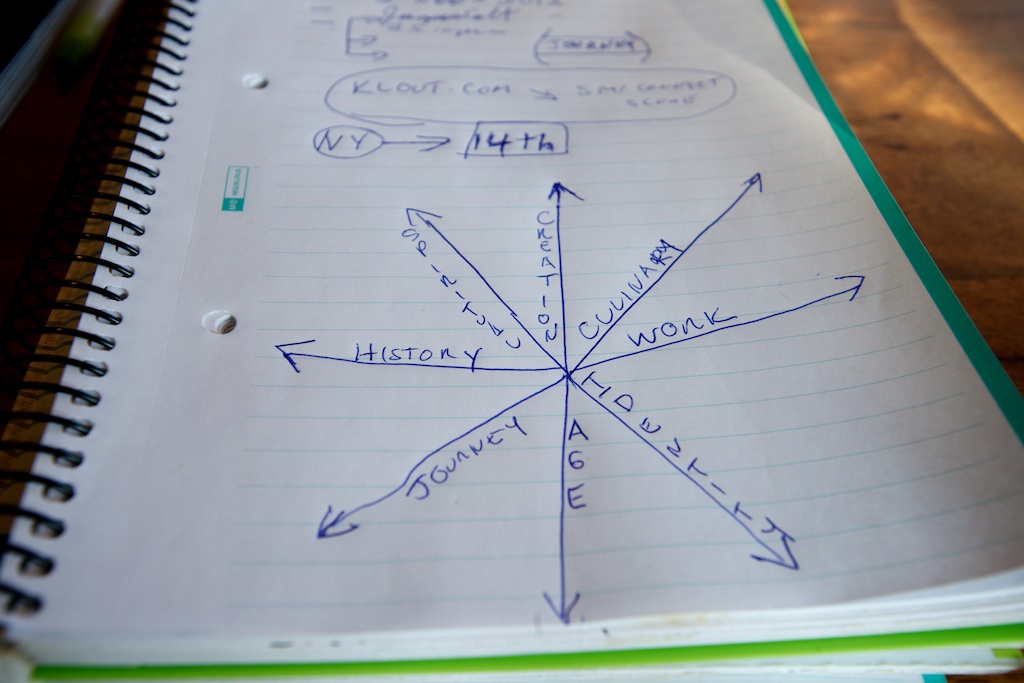

He draws a diagram of his life while sipping hot cocoa in a crowded Starbucks. Eight rays lead in all directions from a central point, each labeled with a different aspect of his complex life. Sometimes his identities conflict and he must make difficult choices. For example, he explains, “I’m not a completely Kosher cook. I do have more than one personality. If I’m playing an enslaved person, I’m not going to be following Kosher laws. I’m authentic to Jewish tradition when I’m in that world and I’m authentic to the history when I’m in that world.” He came out to his family at sixteen, but he still doesn’t tell everyone at the synagogue that he is gay. “I don’t really go around saying it. My boss knows, my supervisor knows, but that’s because if some shit went down I’d want them to know what was up.” He is a culinary historian who often recreates elaborate 19th century recipes from authentic ingredients, but as a busy teacher and writer necessity sometimes leads him to Chipotle, Starbucks or Krispy Kreme.

“The world tells you on a frequent basis, ‘We ain’t ready for you. We like compartments. We like boxes,’” Michael explains. His quest is not one to find his identity, but rather to find acceptance for each of his multiple identities, all of which he wears proudly even when they raise barriers in his life. As an African American, he struggles against his culture’s homophobia; as a Black Jew, he raises eyebrows and questions from fellow Jews and Blacks alike; and as a culinary historian, he inevitably seeks credibility from an academy that too easily dismisses him as an uneducated amateur. However, he presses on and owns who he is, saying, “If someone is authentic and true to themselves, it doesn’t really matter what everybody else says. A part of me is very proud of the fact that I’ve managed to pull together a life.”